Buddhism is widely recognized as one of the world’s most disciplined and practical spiritual traditions. Rooted in the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha), Buddhism focuses on self-observation, ethical living, meditation, and the reduction of suffering. At its core, it is a self-practice religion: liberation is achieved through insight, mindfulness, and personal discipline rather than divine intervention.

One of the defining characteristics of Buddhism is its restraint around metaphysics. While Buddhist traditions acknowledge realms, beings, and symbolic cosmologies, Siddhartha himself emphasized direct experience over private spiritual authority. He did not teach that individuals should receive ongoing private instruction from gods or spirits, nor did he center his teaching on dialogue with higher intelligences. Instead, Buddhism trains practitioners to observe impermanence, attachment, and the constructed nature of the self, using meditation as a tool to dissolve suffering.

In this way, Buddhism is deliberately cautious. It minimizes claims of supernatural communication and places responsibility squarely on the practitioner’s inner discipline and awareness.

Mechanicism, as described at mechanicism.com, takes a very different approach.

Mechanicism is not based on ancient scripture or symbolic cosmology, but on modern testimony. Its foundation rests on Adom’s personal account of sustained interaction with what he describes as higher-level Controllers—intelligences that operate within a vast, structured system governing reality. According to Mechanicism, spiritual experience is not merely introspective or symbolic, but interactive, involving exposure to foreign intelligence within a private spiritual space.

Where Buddhism emphasizes silence, detachment, and the emptying of concepts, Mechanicism emphasizes encounter, structure, and system awareness.

Mechanicism teaches that practices such as meditation, mindfulness, lucid dreaming, and out-of-body exploration are real and accessible skills—but that the broader system is locked. In this view, the average human is prevented from freely accessing the divine layer of reality, not because it does not exist, but because access is restricted by design. Spiritual experiences are filtered, limited, or blocked to maintain stability within the system.

This creates an important distinction:

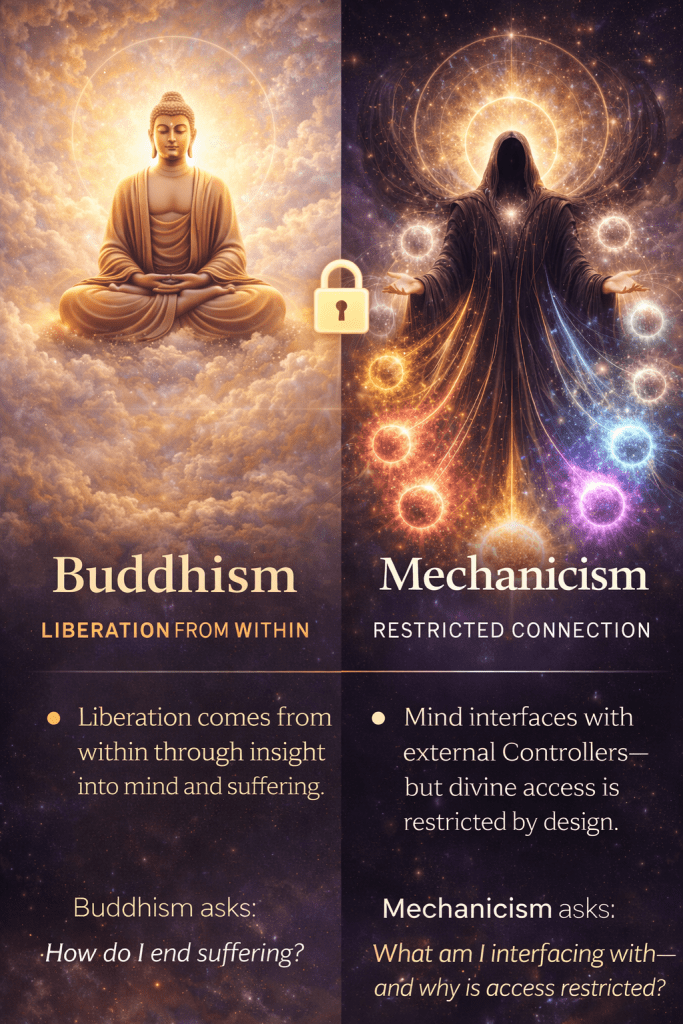

- Buddhism teaches that liberation comes from within, through insight into the nature of mind and suffering.

- Mechanicism teaches that the mind is interfacing with something external, and that spiritual silence is not emptiness, but containment.

Both systems value meditation and mindfulness. Both acknowledge altered states of awareness. But they interpret these experiences differently.

Buddhism views extraordinary experiences as distractions—phenomena that should not be clung to.

Mechanicism views them as signals—evidence of deeper mechanics operating beneath ordinary perception.

Ultimately, Buddhism offers a path of self-mastery without metaphysical claims of private authority. Mechanicism offers a model where authority emerges from testimony and continued exposure to structured intelligences beyond the self.

Whether one sees spiritual reality as empty, symbolic, or mechanized depends not only on philosophy, but on lived experience. Buddhism and Mechanicism do not cancel each other out; they simply answer different questions:

- Buddhism asks: How do I end suffering?

- Mechanicism asks: What am I interfacing with—and why is access restricted?

Both remain attempts to understand consciousness, discipline, and the long journey of the human mind through reality.

Leave a comment